Imagine you are at a carnival. There is a target you need to hit with a bow and arrow. There is also a blindfold which you have to wear. The person running the stand shows you where to aim and models themselves doing it perfectly and hits the bullseye. Now it’s your turn. You have 10 attempts. You also have the choice between two different scenarios you can choose between.

Scenario A – You can remove your blindfold after each attempt to see how close the last shot was.

Scenario B – You have to wait until all 10 of your attempts are up before removing the blindfold.

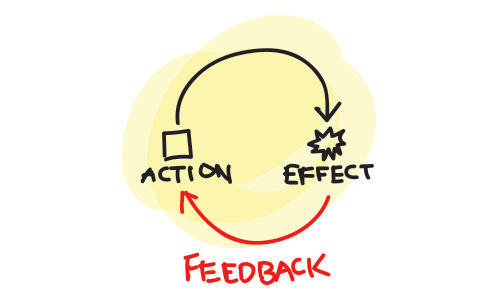

Which scenario is going to yield the better result? Undeniably, it’s going to be A. This is despite both involving the exact same modelling and equal opportunities to practise. It’s because A has the advantage over B in allowing you to adjust your practice based on the near-instant and ongoing feedback.

Let’s call scenario A an “independent feedback loop”. This is where the user receives feedback which they can act upon instantly with no direct input from another expert needed, and now let’s move this into the classroom. How do independent feedback loops play out at school.

Some subjects lend themselves naturally to these loops. When teaching a serve in tennis, certain techniques in art, music, DT…. The practical subjects where there is a clear model of excellence and the user can see instantly the difference between what they are producing and what they should be producing. Compare this to completing a set of maths questions, analysing an historical source or writing a piece of fiction and suddenly the benefits of an independent feedback loop disappear. The question of this piece is, for situations like those just mentioned, can an independent feedback loop be created and, if not, what’s the closest we can get to simulating one?

Let’s start off with a maths example. Scenario B would translate as students working away at 10 questions and then, once they are all done, the teacher shows the answer to the class and they find out how they have performed. Some might find out they have got everything wrong, some only parts and others might be relieved to get 10/10. For those who got some or most wrong, their time spent practising at best was a waste and at worst has helped embed some misconceptions which might move learning backwards for them. Now, if a lesson does get to this point, the teacher would have a variety of options open to them, but this article is exploring if anything could have been done during the practise phase of the lesson.

Subjects where there is a pre-determined correct response.

1. Don’t wait until the end to share the answers: When questions involve multiple steps and there is no way that students could just pluck the answer out of thin air, there is no harm in sharing answers alongside the questions straight away. The usual safeguard of protecting against copying is not needed since the working out is what will hold them accountable. If questions can be solved with no need to show working out, then having an “answer bank” which has all the answers but in a random order displayed, can achieve a similar effect whilst maintaining high levels of accountability. What this won’t do is tell the students where they went wrong. It might encourage them to check their work and they may be able to self-correct. At the very least though, they will know they need some help before continuing.

2. Combine the above with backwards faded examples: If the problems require multiple steps to complete then, by using backwards faded examples which add an extra step as the questions develop, combined with answers being shared, leaners will be able to pinpoint the exact step at which they have a gap in their learning. That knowledge combined with clear notes or examples, should help them self-correct. The worst-case scenario here is that the student knows specifically what they can’t do but is unsure on how to correct it.

3. Build self-checking mechanisms explicitly into the task: If it’s possible to equip learners with the skills to check their own work, that would be ideal. In certain questions where answers can be self-checked with substitution or some other process, teachers should make it an explicit part of the task that is being completed. Instead of the question only saying “solve this…”, including a part which says “using substitution, check your answer”. Estimating answers beforehand can also be a useful tip.

Again, do not rely on learners doing this themselves, adding in an initial part as “estimate your answer to the question” before asking them to solve it, will help encourage these behaviours. Estimating and checking are both things learners are often asked to do implicitly but without making it an explicit part of the question it will not happen and never become a habit. Too often students will do the minimum required of them so if the wording in the question (the ultimate source of authority here) doesn’t ask for something, it is less likely to happen.

Subjects where there is no one right answer and also no in-built independent feedback loop

1. Clear and sequenced success criteria: Giving learners explicit success criteria to hit at specific points can help them self-assess their work. Giving a physical checklist containing targets like “in paragraph 1 make sure you include…” or “in your final paragraph make sure you refer back to…” can help learners assess and improve their work as they move through it. Where the success criteria is less pinned to a specific part of their work, a checklist can do the same thing. Asking learners, after an allotted amount of time, to highlight in their work where they have hit the criteria that they are aiming for can help them reflect and improve.

2. Share examples and non-examples before the end: Pausing learners and sharing some great exemplars and some misconceptions can also help learners reflect on their own work. Again, it’s important this is done before the end of their allotted practice time. When doing this it is important that the teacher ensures everyone understands the underlying properties that make the work being shared good or bad. Everyone’s work will be different and it’s important that the essence of what makes it great or not is discussed, beyond just the superficial content of the work.

Summary

Teachers can do a lot before independent work starts to check learners are as ready as possible and they can do a lot after independent work finishes to rectify any mistakes that have emerged. Let us not forget that there is also plenty that can be done, through careful thought and task design, to ensure that time spent practising is always time well spent.

I’m always interested in what people make of this so please feel free to comment with thoughts, questions or incomplete musings. Follow this or my Twitter account Teach_Solutions for similar content in the future. Also, check out the rest of this site, there’s some good stuff knocking about the place.