A while ago I wrote a blog aimed at giving tips on how to start strong with a new class at the start of a year, it’s here and was called “Starting Strong”. As the countdown to exams have started it felt right to close the loop with this one.

Here are some dos and don’ts for working with pupils as their exams beckon. I am going to focus this around Y11 Maths in England but I suspect it wouldn’t take too much work for someone to decide what parts would apply to them with a different subject/country/age-group.

Let’s start with 7 “don’ts”. These are things I see often enough that they warrant a warning sticker.

Don’t make them sit paper after paper

It’s important to remember that students aren’t going to start learning any differently just because exams are nearer. Don’t put one lesson a week aside for them to complete an exam paper if you haven’t had time to address all the major gaps in their learning from the last one. This is a form of “means end conflation” but getting them to sit lots of papers is not necessarily going to make them any better at completing them.

Don’t review papers by going through them one question at a time

If students have completed a paper, it isn’t a good use of their time to simply see the teacher go through it on a visualiser whilst they self-assess. If the pupil has got a question correct, they learn nothing. If they got it wrong, they need some teaching and purposeful practice on whatever the concept is. If students learnt an idea by simply seeing a teacher complete one very specific example one time and then moving on straight away, teaching would be a very easy profession.

Don’t intervene by grade

Don’t make intervention groups purely based on grade. Identify key areas of curriculum weakness and group them by these where possible.

Don’t assume students know how to revise

Don’t set homework of just “revise” unless you have explicitly taught them how to do this. Even then, be as specific as you can.

Don’t overload them with resources

It isn’t helpful to give them 2 revision guides, 6 exam papers, 10 knowledge organisers, and 3 websites to use. Yes, you will give students all the tools they may need but this is overwhelming and lacks accountability. Keep things tight and achievable. Find one or two great resources and invest in these. Less is more.

Don’t try and cover everything

It isn’t ideal to cover every aspect of the curriculum if it means a large part of it won’t be learnt well. Making the hard decision to cut content, but learn fewer things well, can lead to students performing better in their final exam.

Don’t think you’ve ever “completed” the curriculum

This one is just a little bugbear but I often hear the phrase that a certain class has “completed/finished the curriculum”. I then look at data and they aren’t all achieving 100%. It makes me wonder in what sense the curriculum has been completed. It would be equivalent to painting a patchy first coat of paint on a wall and saying, well, I’ve covered the whole wall so I’m lost for what to do next. The curriculum is not a thing to be completed, it’s a thing to be taught, studied and learnt.

Let’s move on to some “dos” then. Some of these are a cheat because they are the opposite of some above but, it still counts. Most link to bigger ideas in blogs I’ve written previously. Check any out that you may be unfamiliar with.

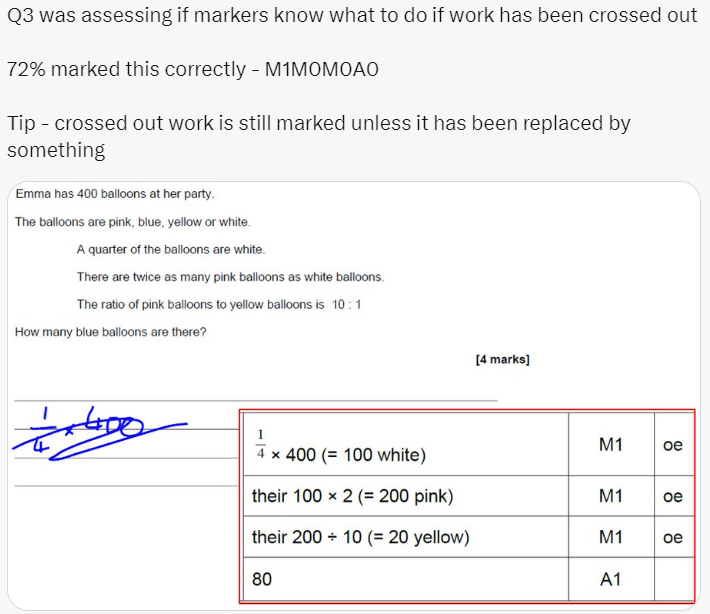

Focus on exam technique

Knowing the course content is one thing, but there will be advice you can give which is specific to the way the exam is assessed or written. I think, in maths, the difference between two students with equal maths knowledge but with opposite exam techniques can easily be a grade. See here for how to get more marks on a maths paper without knowing any more maths.

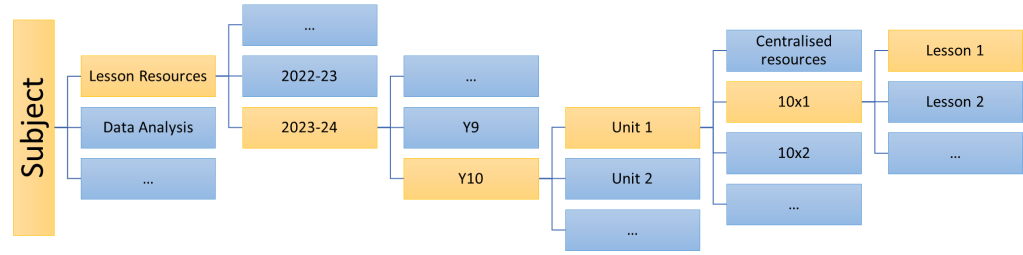

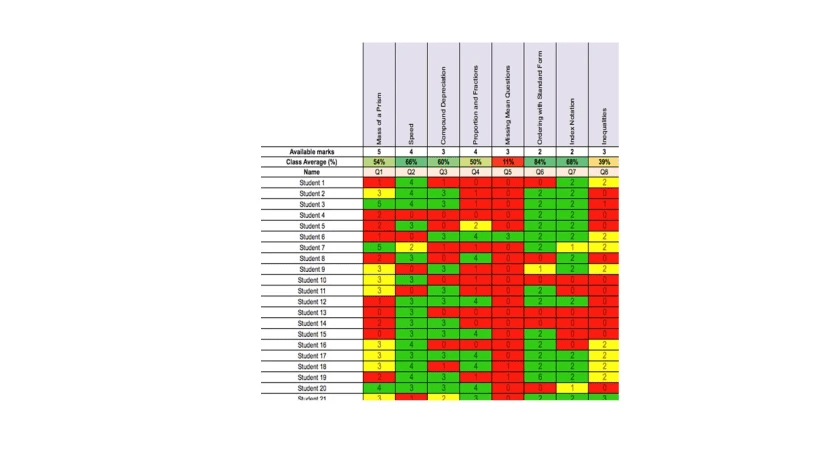

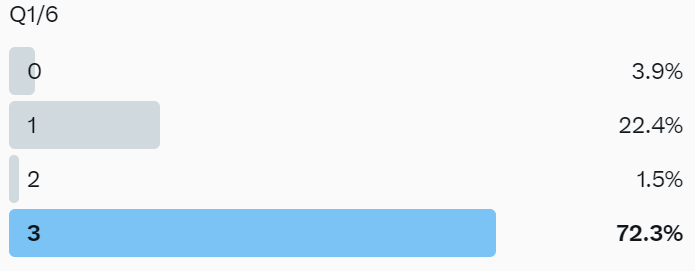

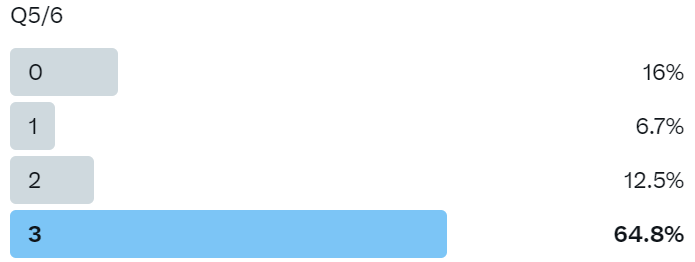

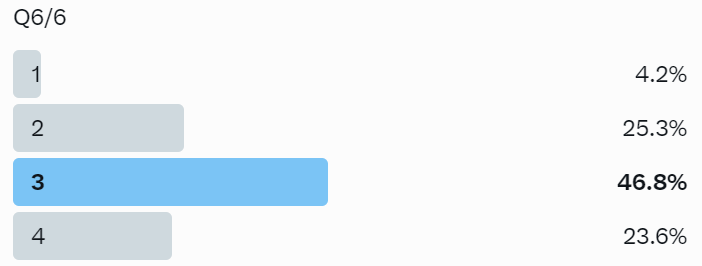

Use QLAs effectively

Instead of going through an exam paper from front to back, use QLAs wisely. Advise on that here.

Share your plans with the students

When you’ve created your plan for your final run of lessons, share this with pupils. That knowledge, combined with them having ownership of their own most up to date QLAs will let them know the small subset of topics that they will need to revise independently because it won’t be covered with everybody in class.

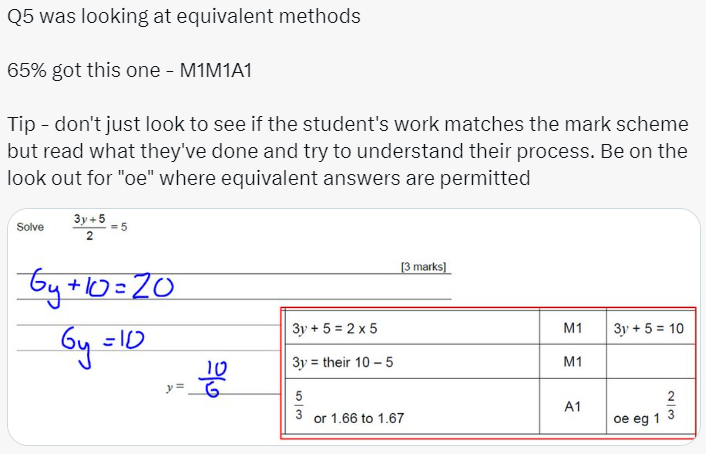

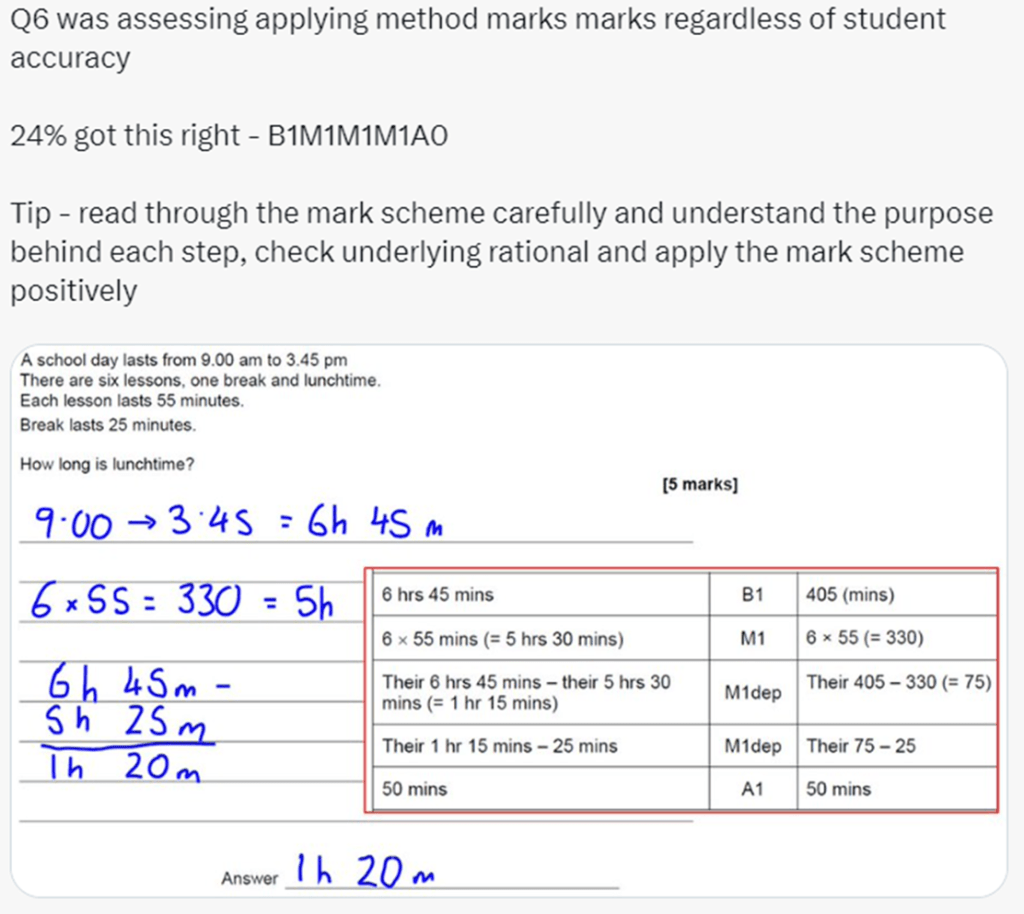

Feedback effectively to assessments

I wrote in the “don’ts” the ways you shouldn’t feedback to an exam, here’s how to do it well.

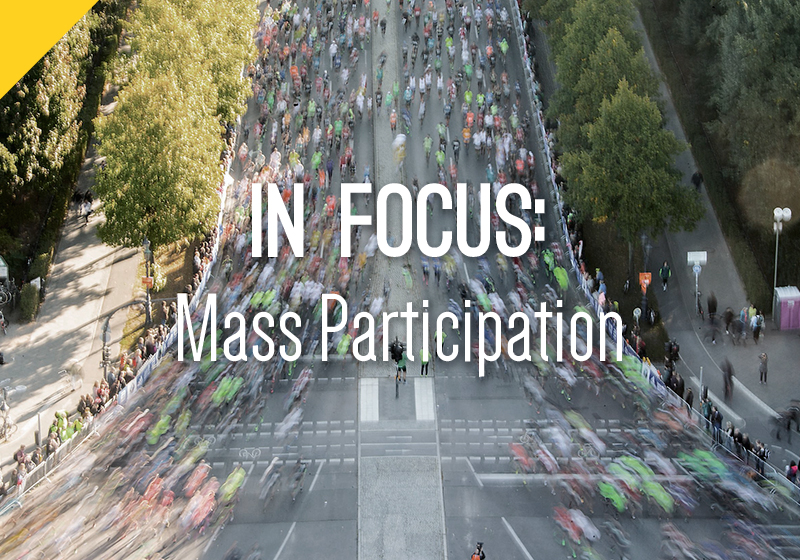

Teach them how to revise

Revision is hard and effective revision can sometimes be counter intuitive. Teach them how to revise. For more on that, see this blog.

The Main Point

It is so tempting to feel the need to drastically change things up as exam seasons gets closer and closer. It is your job, ultimately, to still teach students how to do things they cannot do. This has been your job all through the year with every year group you teach. Hold fast and carry on doing the same thing. Keep the balance of modelling and practice. Keep the balance of checks for understanding and responsive teaching. The only thing I can see a good argument for changing is the ratio of time spent retrieving content, simply because by this point there is so much more to retrieve. It can be hard to resist the urge to change things up but if you believe you’ve been doing a good job for students the rest of the year, there is nothing special that needs to happen. Hold fast. Stay the course. You got this!