Is education a team effort or an amalgamation of solo endeavours? Whilst it can very much feel like the latter, done right, it has to be a collaborative mission, albeit an often lonely one. This post explores ways we might be able to make teachers feel part of a team.

Is education a team effort or an amalgamation of solo endeavours? Whilst it can very much feel like the latter, done right, it can and should be a collaborative experience, albeit an often lonely one.

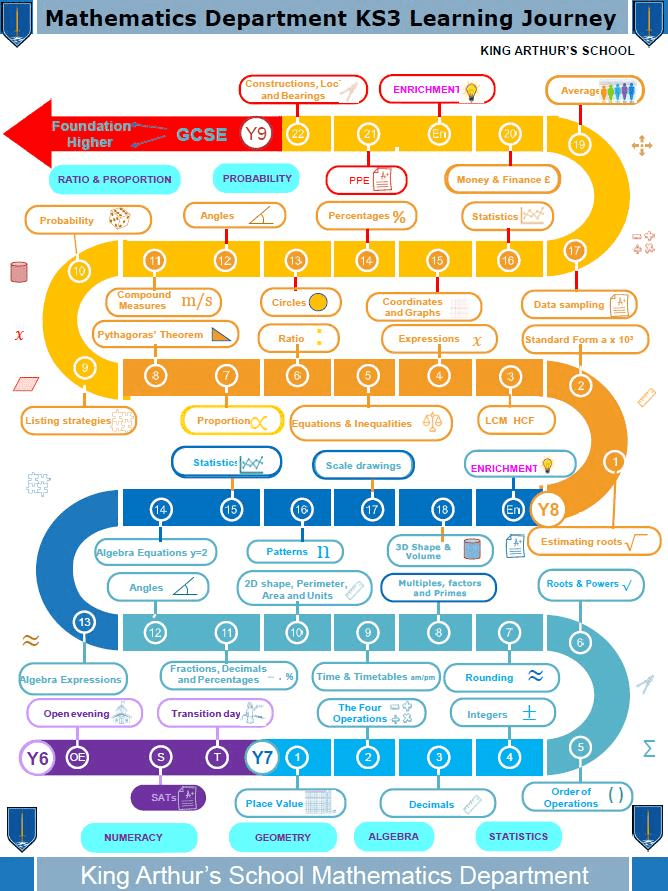

In this post I’m going to ramble for a bit about my past then highlight 3 areas I think schools should be united on: behaviour, curriculum, and teaching & learning. I will also highlights ways in which teachers can be more aware of what is happening in others teachers’ classrooms so they know they are part of a team and not a soloist.

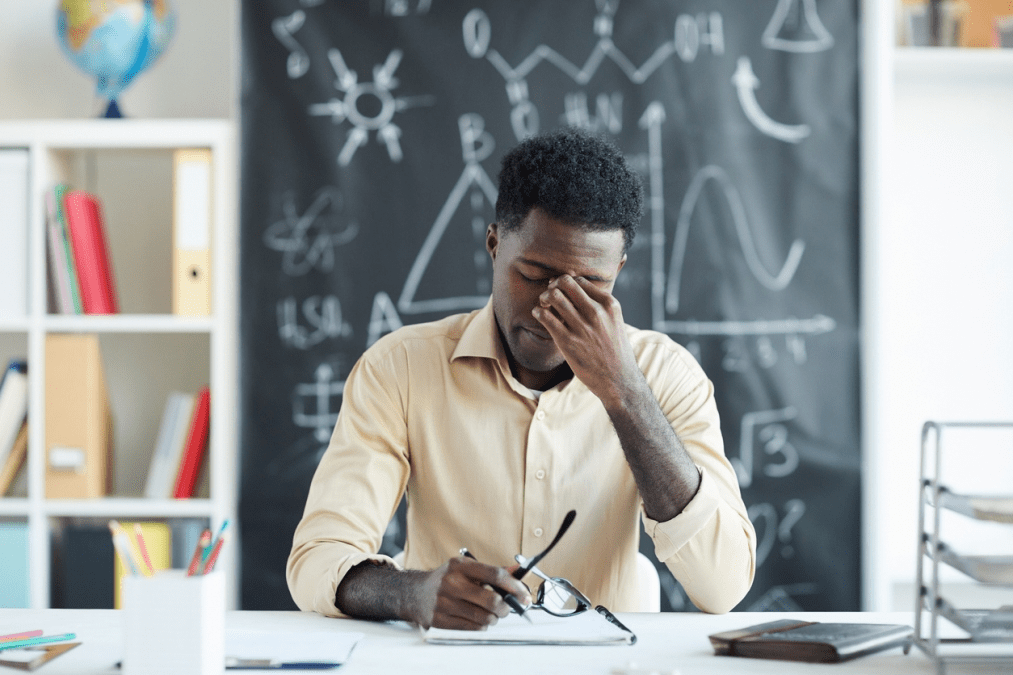

My Shameful Past

When I started teaching I didn’t see it as a team effort. I thought of my lessons as existing in isolation from everyone else’s. I would try my best to get through my day, teaching how I wanted, dealing with behaviour any way I could and embedding (or not) my own routines with my class. As long as I got through my lessons, through whatever means, I felt that I was doing my job well.

My favourite technique for managing behaviour was the “last 3 game”; this was borrowed from my old science teacher and wasn’t implemented in any other classroom. The rules were that the last 3 students to speak out of turn in the classroom would receive a detention. Names would go up on the board once the “game” began and then, once the 4th person spoke, their name would be added and the 1st removed. It worked wonders for controlling behaviour but I was only thinking of the consequences of this within the walls of my classroom.

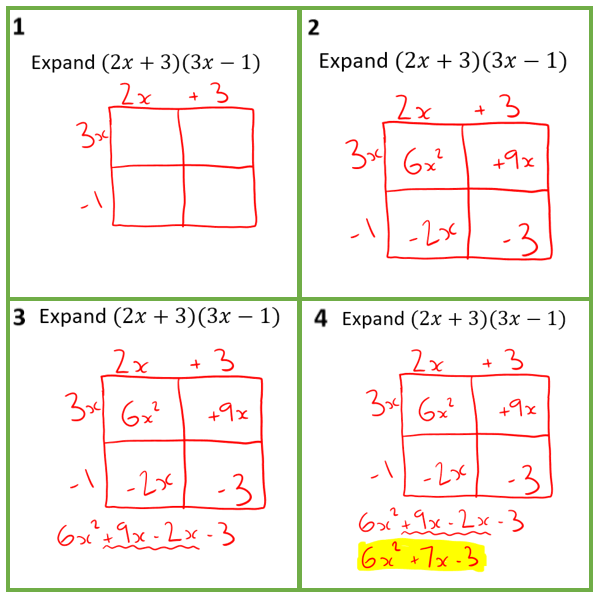

I would also teach using methods and approaches I felt were best regardless of what they had already learnt. FOIL became the grid method, BIDMAS became order of operations, SOHCAHTOA went in the bin.

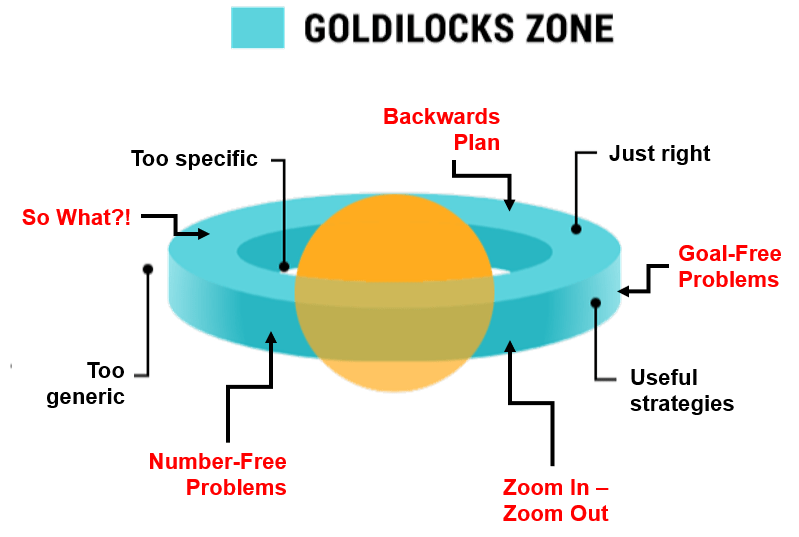

Great Schools

In my defence, it’s not that I was deliberately ignoring any school-wide practices, it’s just that there weren’t many. Thankfully, this seems to be changing. The best schools aren’t built with the flexibility to cater to every teacher’s whim. They are built with the students in mind; knowing that there are some things that, if consistent, will be of huge benefit to them. They are also built with ready-made systems that don’t require new or struggling staff to think of their own ways of managing behaviour whilst being flexible enough for experienced staff to still shine.

Your Autonomy Isn’t More Important Than Their Learning

Any good school leader is trying their best to create a team. Yes, we each have our own specialisms, which team doesn’t? But without a team pulling in the same direction there is no chance of a school being as effective as it otherwise could be. If you are looking for a profession where you have complete autonomy AND make the most positive impact you can on the lives of young-people, teaching is not for you.

The teachers in a great school are part of a team. They’ve learnt the same set-plays, have the same philosophy and look out for one another. The difficulty is that teaching is so often done in isolation of any of your teammates that it can too often feel isolating and those set-plays can quickly collapse with the fear of you being the only person trying to implement them.

Some (Brief) Practicalities

Let’s explore some of the ideas that should be coordinated across a school and look at ways you can make all staff feel like they are part of a team.

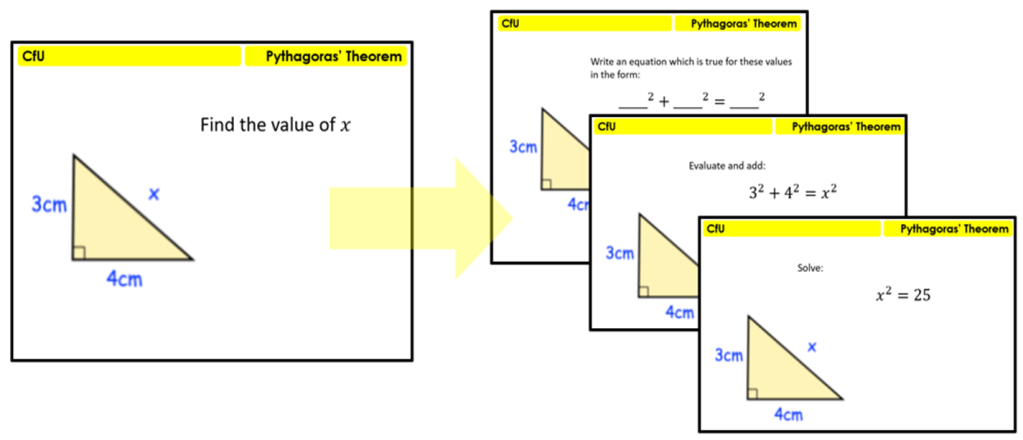

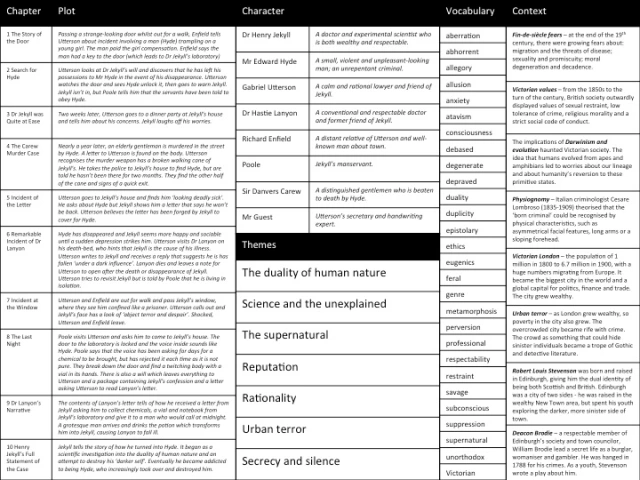

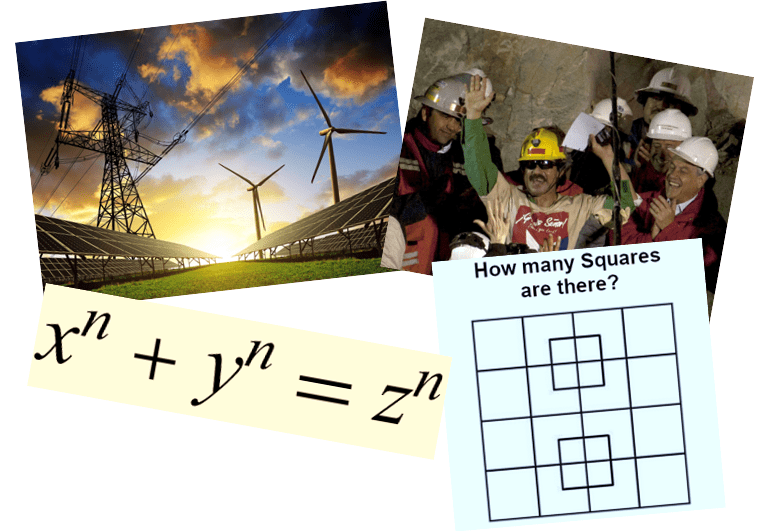

Curriculum

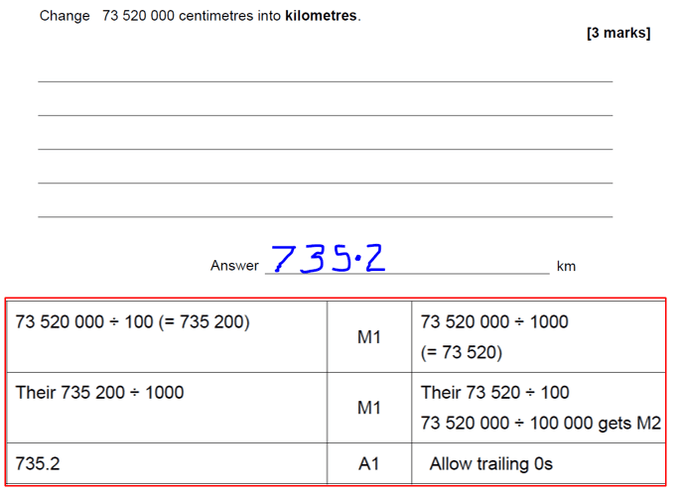

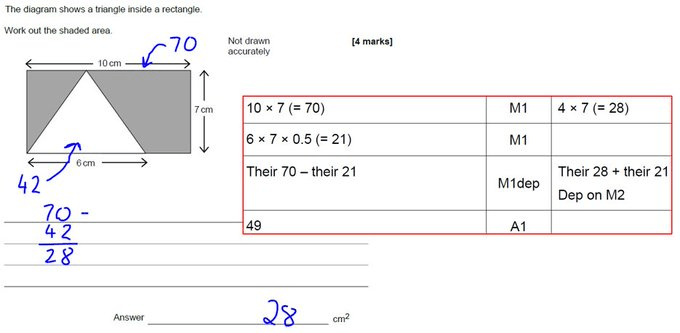

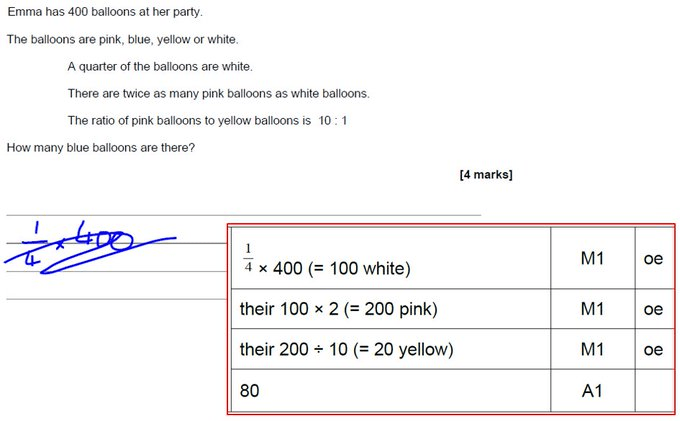

WHAT: The models students are taught, the ways they structure essays, the mnemonics used… needs to be uniform across a subject (or across multiple subjects if possible).

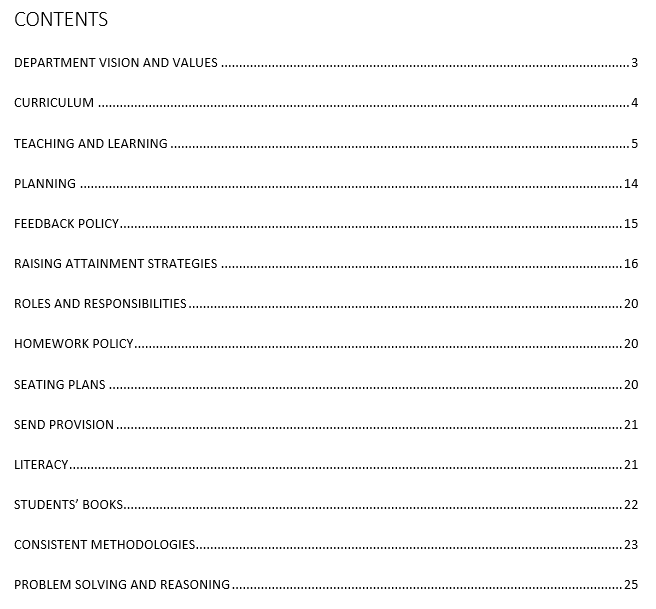

WHY: Without this, students will not be building on knowledge as effectively or efficiently as they should be.

HOW: Having the HoD create a document which contains this standardised ways of working should ensure all the team know about this. Ensuring that centralised lesson resources use these processes helps with consistency too.

SHARING: Joint book looks, co-planning and lesson drop-ins are all things which can be done to help staff know they are not the only ones delivering content in this particular way.

Behaviour Routines

WHAT: Habits of attention, rewards, sanctions etc should all be standardised. Not just the systems that are used but also what a student has to do to be recognised (positively or negatively).

WHY: Students deserve consistency. Not only will it make them feel safe and secure, by not having the goal posts move every lesson will help embed the positive behaviours you want to see them exhibit.

HOW: Getting into the minutiae about this is vital. School-wide training should involve various scenarios with a chance to script and practise responses. Staff should have the chance to clarify anything that needs clarifying and work on personalising the necessary responses to their own turns of phrase and personalities.

SHARING: If certain habits (hands up for silence, clicking for approval…) are to be used with students they they should be used with staff too. This can help foster a sense of team and also act as a constant reminder to staff of what is expected of them.

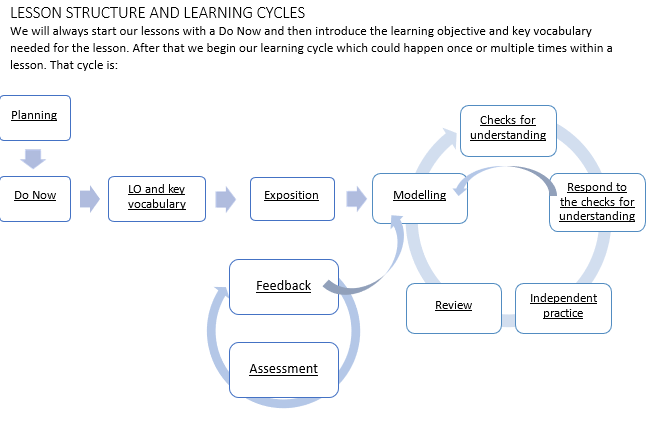

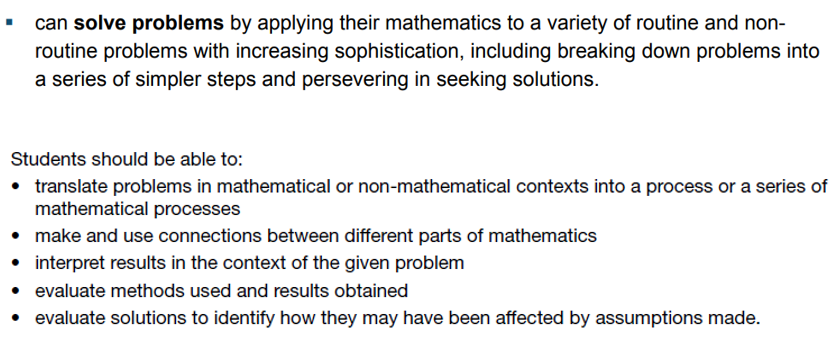

Lesson Structure

WHAT: The raw parts of a lesson, the beginning, middle and end of it, can be centralised with a common language and purpose behind each stage.

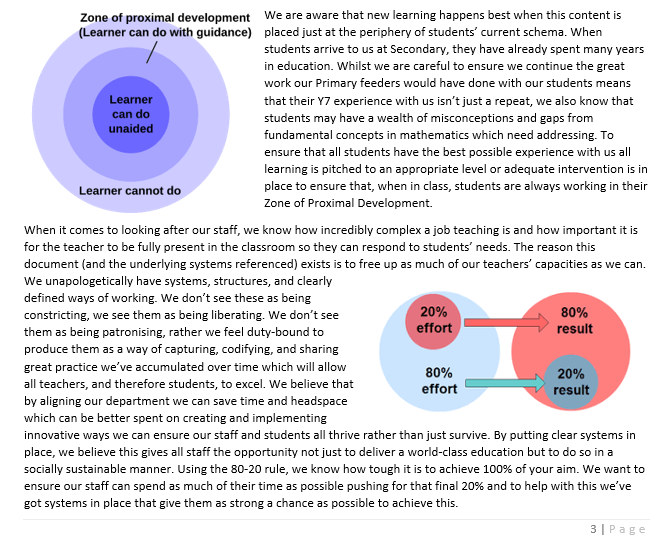

WHY: By having a “default” lesson structure, CPD can be tailored, lessons can feel safe and the excitement and passion can come from the content, rather than any novelties in the lesson itself. Also, teachers are not time-rich enough to produce an incredible and bespoke lesson for every hour that they teach, ensuring that base lessons are of a high-quality is vital.

HOW: Senior leaders should agree on a lesson structure which HoDs can then personalise. This should be shared with all staff in a department alongside the necessary training needed to produce a great lesson that fits this format

SHARING: Co-planning, sharing resources and lesson drop-ins are great ways to ensure that staff know this is happening everywhere.

Summary

As well as considering what systems you want to unify as a school you should also consider how you are going to make sure staff are aware that it is happening, with fidelity, in every other classroom too. Teachers spend so long with students, it can be easy to forget they are part of a team working for each child. Without cohesion and consistency amongst that team, we are letting the child down.

I’m always interested in what people make of this so please feel free to comment with thoughts, questions or incomplete musings. Follow this or my Twitter account Teach_Solutions for similar content in the future. Also, check out the rest of this site, there’s some good stuff knocking about the place.