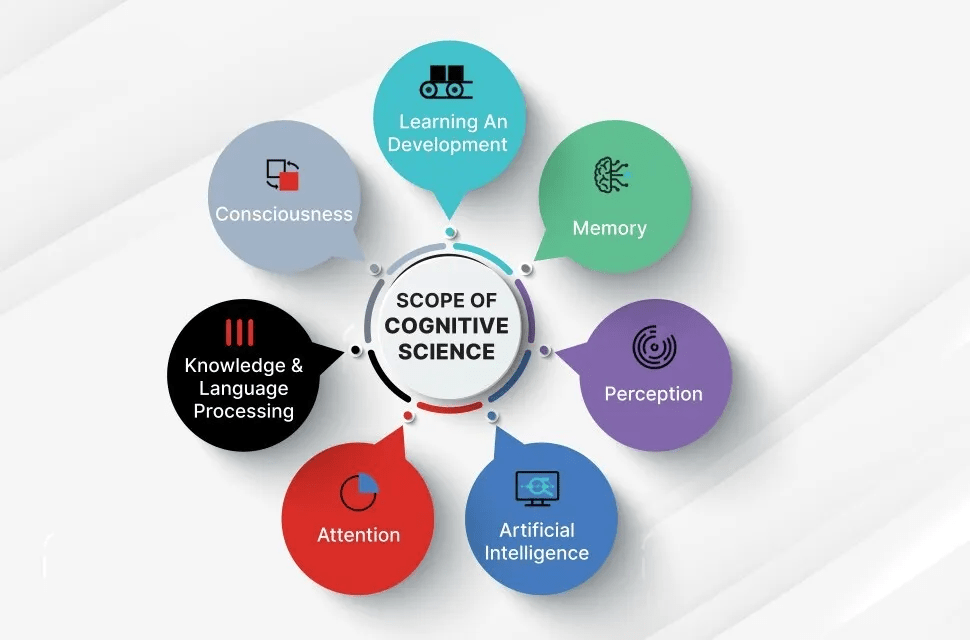

No one quite knows when it started, but for a while now cognitive science has been ever-present in discussions around best teaching practice. If you accept learning to be a change in long-term memory (which even if you don’t it’s hard to argue that it doesn’t have a vital role to play) then all of a sudden this huge bank of research looking into memory and how that part of the brain works is useful.

This blog warns about the dangers of treating cognitive science as a “catch-all” for teaching and asks if there is another domain out there, an unexplored goldmine, ready to shed light on some pedagogical aspects that cognitive science does not cover.

Power of a Shared Language

Ideas around retrieval practice, interleaving, interweaving, dual-coding, explicit instruction, schema, cognitive load… all originate in the realm of cognitive science. These are all great things which have had a huge benefit on education recently for many reasons, not least because simply having a shared language is a powerful thing.

All the ideas above have been written about A LOT. The power of a shared language has allowed teachers that did those things anyway to talk about them more succinctly. It allowed a community to experiment, tweak and innovate all these ideas and apply them to the classroom in the knowledge they were all working on the same thing. It allowed people to codify aspects of teaching and break it down into discrete parts that allow it to be explicitly taught. The ability to talk about an idea without having to show someone it is a powerful thing.

Cognitive Science – Necessary but not Sufficient

Cognitive science is not a panacea, it focuses very inwardly on the processes of the brain. By and large, its studies of how learning happens are done in isolation, in a lab. It misses out a massive part of the realities of teaching, namely, that most of the time it happens in a room full of not 1 but 30 brains. Each of those is living inside messy, illogical, hormonal, confused, unique, incredible, frustrating, funny, brave, unpredictable, bored, inspirational, exhausted humans.

Cognitive science does not exhaustively cover what it takes to be a teacher – not even close; in its defence it has never claimed to, but I do worry about increasingly seeing teaching practice becoming synonymous with cognitive science.

It is a necessary but not sufficient component of education. Its effects will only work if all your pupils are motivated to engage with the content in the first place. That sounds simple enough but behavioural issues are often the biggest barrier teachers face in their delivery of content. No matter how well you know their brain should work in theory, if you can’t get them to engage with the content in the first place it will be, inevitably, ineffective.

Some Unanswered Questions

Some examples of common issues teachers have that cognitive science cannot solve are:

- why do they make silly mistakes when they actually know the answer?

- why don’t students try their hardest on a test despite wanting to do well?

- why don’t they revise when they know it is good for them?

- how do I win a class back that I feel I’ve lost?

- how should I end my lesson?

- how do I get them to behave?

- how do I get them to do their homework?

- why do they make bad choices despite seemingly wanting to learn?

- how do I get them to work on a wet and windy Wednesday?

So does it exist? Is there something which has been studied for decades which contains the tools, tips, and shared language we need to tackle things like the questions above? Something which could be the starting point of a new shared language which could codify and share some of the great practice that already exists? Well, I think it does.

Behavioural Economics

Cognitive science is to learning as behavioural economics may be to behaviour for learning. If you think there isn’t as much or more to be gleaned from behavioural economics than there is from cognitive science then let me try and convince you with the below.

As you go through these, see if they resonate with problems you have experienced. Imagine there being as many books written about their application to education as there are for cognitive science. Imagine having a shared language so people can talk the same language around these things, develop strategies on the same issue, talk concisely to each other about known problems. Imagine these ideas being researched to see what effect there is on learning. Then imagine the power that could have on the educational landscape.

I’m going to introduce 8 ideas, explain them, and discuss implications they could have in the classroom. This is just the tip of the iceberg though. Both in terms of the concepts out there and how the ones mentioned could be used for by schools.

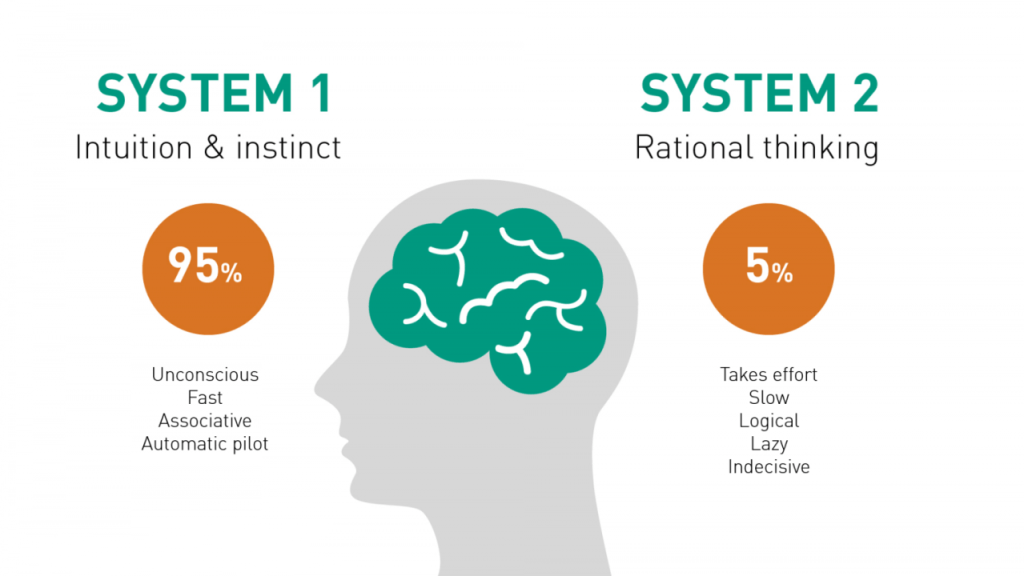

1/8 System 1 and System 2 Thinking

Making students (and staff) aware that humans spend most of their time on autopilot is vital. If you haven’t come across system 1 and system 2 thinking then look into it. It has so many implications for the classroom.

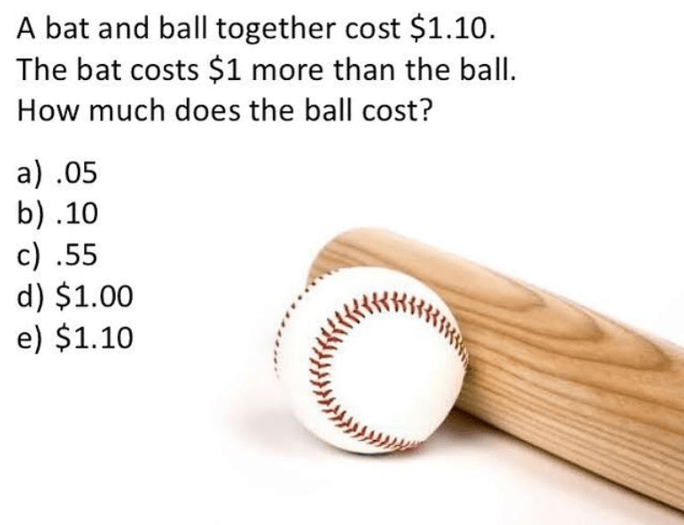

A typical question used to highlight the issues with system 1 thinking is the bat and ball question:

The first time people see this question it is almost impossible to think the answer is not $1.00. A quick bit of maths however shows you that it can’t be the case. What’s happened there? Well, your system 1 brain has chosen the most intuitive answer without doing much thinking about it. System 1 thinking is quiet but susceptible. Forcing students out of this mode is vital to getting the best out of them.

What if I told you this next question is designed to trip you up? It is designed to be as deceptive as the first question:

I’d bet any money this question would have a higher success rate than the first. I also think this would happen regardless of the order the questions were presented. The important thing is that you were jolted out of system 1 thinking and switched to system 2. All by yourself. Imagine harnessing this with students!

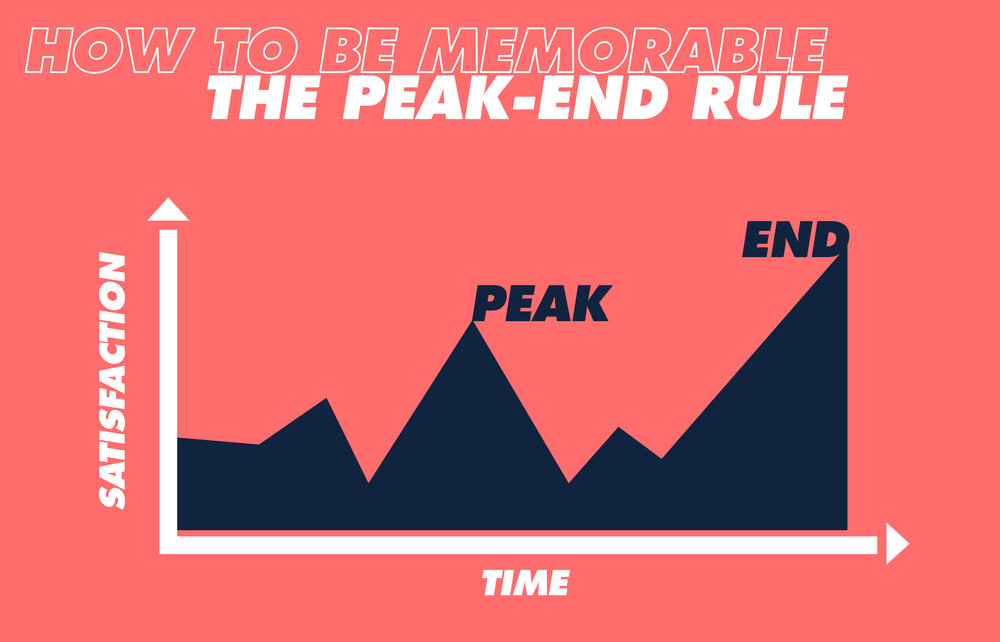

2/8 The Peak-End Rule

In an episode, there seems to be two main moments that stick in people’s minds. The emotional peak (the most intense event during the episode) and the end of the it. If there was ever a reason to really think hard about how your lessons end this would be it. The rule states that how students feel about themselves in relation to your subject is going to be heavily influenced by how they feel at the end. If you are always ending your lesson with the hardest content, what effect might this have? Conversely, if the lesson ends purposefully, with praise being shared and an achievable question being asked, what effect might that have?

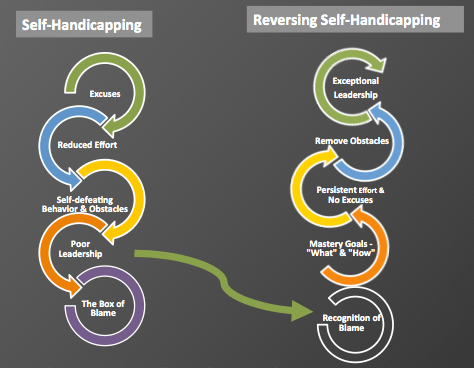

3/8 Self-Handicapping

For all sorts of reasons, humans do not always try their hardest. Deliberate self-sabotage to save face, reduce the effort needed, have excuses for poor performance… is a known phenomenon. Knowing this is the first step to tackling it. Talking about it with students and giving them the language to discuss and address unhelpful tendencies can sometimes be enough to change behaviour.

4/8 Recency Bias

Humans are much more influenced by what has happened more recently. A gambler who has won the last 3 rounds but lost the previous 10 is much more likely to believe they’re doing well than someone who won the first 3 and lost the next 10.

This could have a lot of implications in the classroom but one I think that could be particularly useful is in thinking about how to affect change on a class that you think you’ve lost. Knowing that the last few lessons are going to influence their perceptions on the class much more than anything that’s happened previously should give hope to it never being too late to turn things around.

5/8 Short-Term over Long-Term

Humans are much more concerned with short-term benefits than they are with long-term ones. Students may well want to do well in their exams, they may also know exactly how to revise, putting these two together when their exams are a long way away is not a given though. Creating short-term rewards where you can to encourage motivation may not only be sensible, it may be necessary.

6/8 We Want to Fit In

The desire to fit in can overrule the desire to do what you think is right in the moment. Knowing that if poor behaviour gets the spotlight in the classroom than it may encourage more to join in rather than the desired effect teachers are often hoping for which is to detour it.

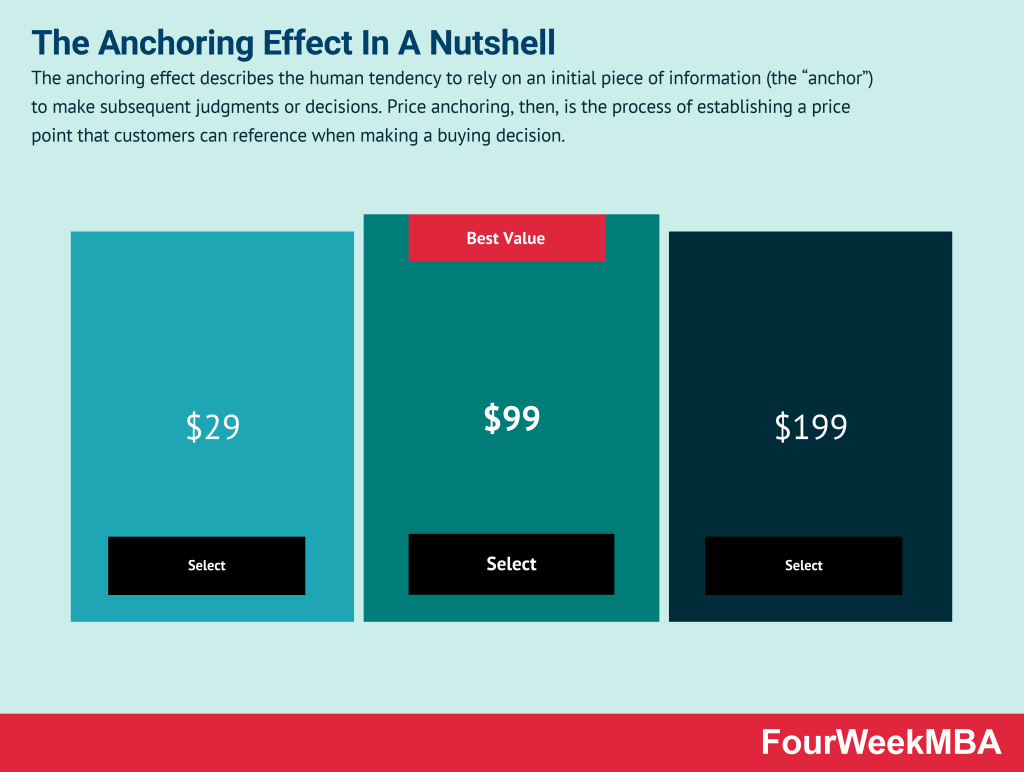

7/8 Anchoring Effect

If you want something to be appealing, have something to compare it to where it looks favourable. The typical example of this is popcorn prices at the cinema. They are all ridiculous but buying a large for £5.80 suddenly seems attractive is a medium costs £5.40. Imagine a cold dark afternoon where you want students to complete 20-mins of work independently. Why not give them the choice between that and 30-mins wort of work independently. All of a sudden that 20-min task makes them feel like winners.

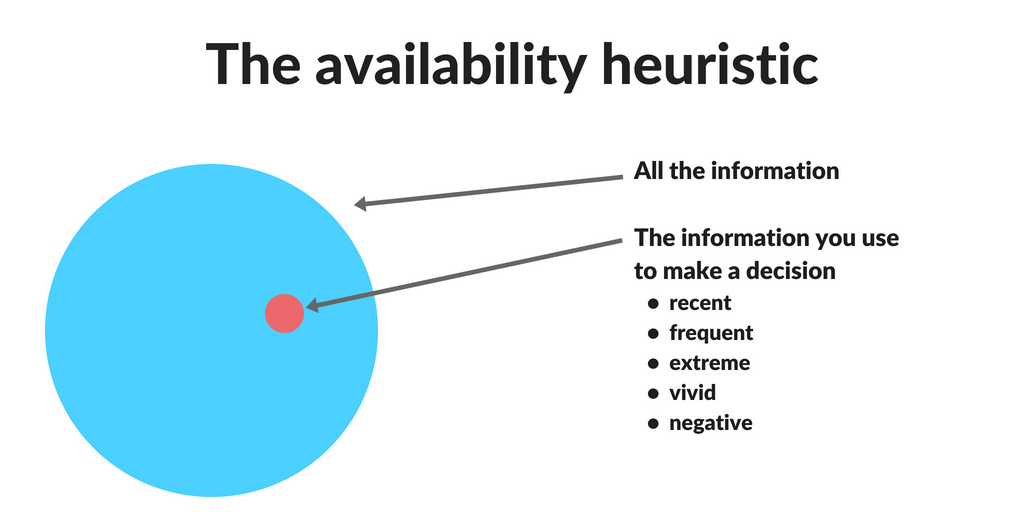

8/8 Availability Heuristics

Humans, it turns out, are really bad at making decisions. If we start to combine ideas like system 1 and system 2 thinking and recency bias you get the begins of ideas like availability heuristics. The notion that we tend to only make decisions based on immediately available information rather than all the known information. Front loading expectations and consequences may then help shift behaviour patterns to be more desirable. Moving to a more proactive rather than reactive behaviour management style can help stop issues before they even begin.

Summary

I hope that at least some of the 8 ideas above resonate with people’s classroom experiences. I think that there is an untapped goldmine of research that is waiting to be applied to the classroom and I can’t wait to explore these ideas further in the future. Cognitive science is incredible for making sure an engaged individual is learning well, behavioural economics may be necessary to ensure that engagement is there in the first place.

I’m always interested in what people make of this so please feel free to comment with thoughts, questions or incomplete musings. Follow this or my Twitter account Teach_Solutions for similar content in the future.